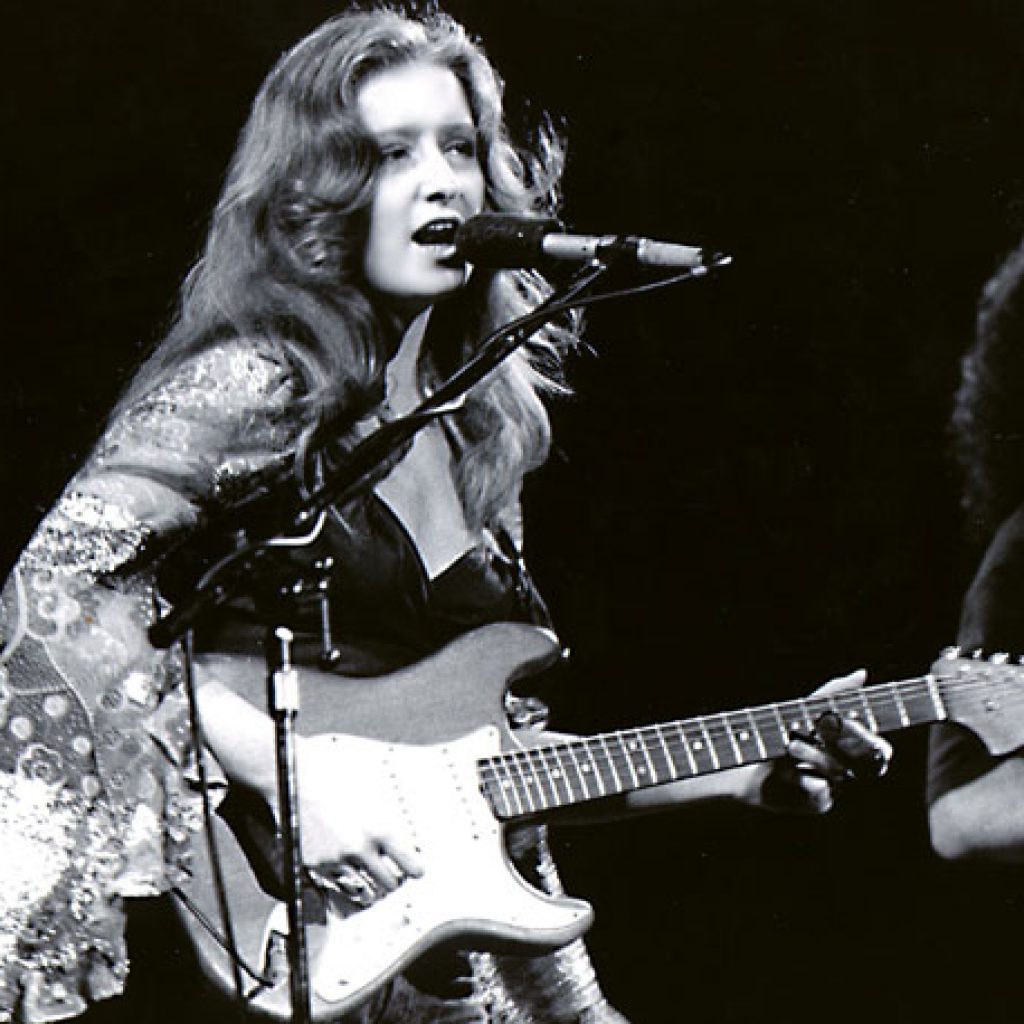

In the 14 years I’ve been writing about and reporting on African music, I’ve learned to pay attention when musicians with a mainstream audience show any glimmer of interest in the subject. After all, it takes a lot of articles, reviews and radio programs to match the impact of, say, Paul Simon’s Graceland in terms of opening American ears to Africa. So I was intrigued when in 1998 I learned that Bonnie Raitt, one of the most admired figures in American blues pop, had recorded a song inspired by Oliver Mtukudzi of Zimbabwe. A Quaker with a Radcliffe education and the daughter of Broadway legend John Raitt, Bonnie first gained international stature during the 1970s when she championed the raw, rootsy blues of American icons like John Lee Hooker, Sippie Wallace and Mississippi Fred McDowell. These, it turned out, were not merely her influences, but her friends and mentors. Raitt’s rich, earthy vocals and sweetly stinging slide guitar were electrifying. She also wrote great songs, and delivered soulful live performances powered by rowdy, rockin’ blues romps, devastating ballads, and a spirit of activism that embraced the anti-nuclear movement, civil-rights causes and the fight to win recognition and compensation for the neglected and cheated black musicians whose music had led directly to the whole rock ‘n’ roll industry. All of this solidified Raitt’s hold on a core audience that she has never disappointed since.

Raitt’s stardom did bring personal ups and downs. After years of hard partying, she went sober during the mid-’80s, and then took a little while to regain her footing career-wise. But her 1991 release Luck of the Draw began a sensational second act that has won her nine Grammy Awards and many more loyal fans. So when I saw that phrase “inspired by the music of Oliver Mtukudzi” in the credits for the song “One Belief Away” from Raitt’s 1998 album Fundamental, I was interested. When I finally got Raitt on the telephone, she astounded me with her knowledge, passion and curiosity about African music. I told her about “Afropop Worldwide,” the country’s first and only national radio program devoted to the music of Africa and the African diaspora. The weekly program began in 1988, so Raitt had some catching up to do. “Afropop”’s creator and producer Sean Barlow and I put together a package of programs and literature and sent it off to L.A. I also sent Raitt a draft of my then-unpublished book, In Griot Time: An American Guitarist in Mali (since published by Temple University Press). I figured that her blues background made her a likely fan of Malian music.

That might easily have been the end of the story. But rather than putting our packages aside along with her mountains of fan mail, Raitt listened, and read, and got back to us. She invited Sean and I to a sold-out concert outside Washington, DC and thanked us from the stage. In 1999, we met for dinner in New York, shortly after Raitt—who by now had become “Bonnie” to us— had returned from the Musical Bridges tour to Cuba. She had been frustrated by some aspects of the experience. It had been too programmed and hadn’t allowed enough time for informal, free-form exploration and interaction. “I bet you guys could do something like that in Africa, and do it right,” she said, fatefully.

“Afropop Worldwide” has been successfully leading listener excursions to Africa for years, and Sean immediately responded to Bonnie’s idea of a trip organized for musicians. He suggested Mali as the ideal destination. At first, Bonnie was leaning toward southern Africa, but after more listening, more reading of my manuscript, and after seeing Habib Koite perform at WOMAD USA in the summer of 1999, she signed on. At first, the plan was to bring a group of musicians. But scheduling difficulties and other obstacles caused those on Bonnie’s wish list to drop out. No problem, said Bonnie. We’ll go anyway.

So, Sean and I took Bonnie to Bamako in January 2000. We spent a week dropping in on musician friends for informal jam sessions, and then we were joined by some 25 “Afropop” listeners and three Malian musicians, including Koite, for a 10-day excursion northward along the Niger River. Bonnie came to this adventure with no pre-conceived agenda. She didn’t want press coverage, or to sign up musicians to record with her. It was critical to her that nothing should leave the impression of an American rock star making a career move by jumping on the world-music bandwagon. Bonnie told us that when she left Radcliffe in the late ’60s to make her first record, she had been working toward a major in African Studies. Going to Africa was a long-held dream and a prospect with deep personal meaning for her. “Afropop Worldwide” was privileged to help make that dream come true.

When we got back, Sean Barlow interviewed Bonnie for “Afropop Worldwide.” Here is an extended excerpt from that conversation. She makes reference to a number of Malian musicians. Djelimady Tounkara (Super Rail Band guitarist, and hero of In Griot Time), Lobi Traore (singer/guitarist), Oumar “Barou” Diallo (bass player for Ali Farka Toure, and an important player in In Griot Time.)

This interview also underscores what an insightful and thoughtful fan and observer of African music and culture Bonnie was and is. What we get in these exchanges is a mix of passion, humor, curiosity and deep intuitive understanding. We can only hope that some of that spirit will manifest in Mali’s future, and the world’s. God knows we need it!

—Banning Eyre

Afropop Worldwide – Mali Magic 2000

tip: most convenient way to listen while browsing along is to use the popup button of the player.

Your Host is Georges Collinet

In January, 2000, a group of adventurous Afropop listeners accompanied by local artists including Habib Koite and special guest Bonnie Raitt toured Mali to hear the country’s extraordinary music. This program recaps the adventure with vivid live recordings of Habib, Khaira Arby, the Super Rail Band, Lobi Traore and others in nightclubs, private homes and in the dunes of the Sahara. It was a trip that could never happen today, but close your eyes and listen, and you’ll feel the magic.

Produced by Sean Barlow and Banning Eyre.

Featured Artists

- Super Lolo

- Souleymane Sidibe

- Mah Kouyate

- Dogon Boys

- Dogon Dancers

- Djaba Regional Band

- Oumou Samare

Interview by Sean Barlow ★ Photos by Banning Eyre

Sean Barlow: In the big picture sense, what was your impression of Mali?

Bonnie Raitt: I had read Banning’s book before I went, and in fact during my trip, I would wake up in the morning and read about the cast of characters I was going to encounter that day. It was so much more friendly and welcoming than I was expecting, because usually I’m on tour and there in a professional capacity … this was different because it wasn’t like being on tour or a tourist on vacation.

The great gift of Banning’s having lived there and Barou advancing me coming was that by the time I actually got to meet Djelimady and Lobi, they were welcoming me because they’d seen my [live] video. We’d sent an advance party with my cds and [Roadtested] video so I felt like I’d earned the respect of the musicians on the basis of my musicianship, not on my fame. That made all the difference because I was welcome as a musician and as a person.

My overall impression of the country is it’s [so] free emotionally … the music pours out of the musicians, the humor pours out… the affection they have for each other, the lack of self-analytical neurosis that we get in the West a lot. It was just really refreshing for me to be in a country that’s run by the people who’ve lived there for thousands of years, instead of having to show up in a place where you feel guilty that you’re the ruling class that ruined their country. That made a big difference immediately to me … that I was in their country and there wasn’t any resentment of me being there.

Q: Let’s talk about some specific artists; in terms of your experience when you play with them—let’s start with Djelimady Tounkara.

A: Well, it was the second day we were there, and I knew that we were going there for lunch that day. And of course Banning had prepped me and I’d read the book, which is primarily about the Tounkara family and about Banning’s experience living there for seven months. So he |Djelimady] was legendary in my eyes at that point and I’m sure was not aware that I knew as much about him as I did.

So when I saw his wife and his family in his compound, for me it was a great honor. It was like when I used to go to Detroit and go to Sippie Wallace’s house, or visit Junior Wells, Buddy Guy or Fred McDowell in his home in Como, Mississippi. It was the equivalent of jumping into another culture and being immediately welcomed. And then we whipped out our guitars, that was a real thrill for me. To get to actually experience what he’s like, having read Banning’s beautifully illustrated accounts, to actually hear and watch it in person and see the obvious chemistry these two guys had and the how much joy they had at seeing each other again.

And then to add my own unique cayenne pepper to the mix there—because I don’t know if anyone was really prepared for what the slide guitar is going to sound like, including me—so it was enveloping and astounding to be in a room surrounded by Djelimady’s family and musicians and just immediately start playing. It was no pressure, no attitude, no anything, no agenda, just absolute pure joy of music.

Q: What about Djelimady’s technique? What do you remember or observe about how he played guitar?

A: Peals of licks, I think, was the expression I read about it. And the times I saw him play with the Rail Band in nightclubs and in his home … he doesn’t play like anyone else I’ve heard. He made little nods—we’d play some blues and he would do some sort of George Benson, jazzy thing. I could tell that he had an incredibly deep and wide vocabulary musically, but it was indecipherable what he was doing. I don’t study the guitar, I just play instinctively, so for me to watch that close and hear what was coming out of him was astounding.

Q: Peals of licks, yeah, that’s good.

A: Yeah, they peel off his fingers, it’s just like a cascade; absolutely beautiful, and so original and so inventive. Of course I don’t have the context that you or Banning have to know how original he is but I know I’ve heard lots of guitar players and I heard some of the most astounding choices I’ve ever heard anyone make in a complicated rhythmic, many guitared band, with a lot of stuff going on.

What he chose to play that night in the club with his band … I came up to the stage, was crouching up, kneeling in front of those guys to give Djelimady some money [as the audience does frequently in Mali], and I actually just stayed up there so I could distinguish between what Banning and the other guitarists and Djelimady were doing. He looked right at me—at this point we were peers—and did some stuff I’ll never forget.

Q: Let’s talk about Lobi [Traore], at Ma Kele Kele.

A: Well, again, I’m not out to promote Banning’s book, but I loved the description of them finally finding Ma Kele Kele and encountering wild pigs walking around near the bandstand; the whole visual of the place with the thatched bar. The scene in Mali reminds me of being in San Antonio or some roadhouse out in Texas, where the nightclub, the bar where you go stand and order a beer, is some sort of thatched roof or some sort of makeshift corrugated roof to keep the sun or the rain off the person serving. The dance floor is just basically trees and dirt, the band was on a slab of cement in the middle with some Christmas tree lights strung up over the top. So it gives the impression of being an outdoor wingding someplace way outside of town, which is what it is. But normally in West Texas, you don’t have wild pigs walking around that are going to be eaten if somebody orders from the menu.

The atmosphere was very sensual and it was a balmy night…. One of the cool things about Mali is how OK it is to be a woman dancing without a partner on the dance floor. There were lots of younger people that night at Ma Kele Kele and there was no weirdness with foreigners just jumping into the fray.

The music is so hypnotic and haunting because of that [pentatonic] scale, that type of Bambara music. The way Lobi plays is something that really moves me because it’s so blues—the same thing I like about the blues is the same thing I like about Lobi’s playing. He has a very interesting hybrid of rock and African and blues in him and he’s original in a way that I’ve never heard, his tone and what he plays where. And his band is unbelievable.

So it was about as, as—I don’t know what the word would be, I don’t want to say erotic because that’s too limiting, but in the bigger sense of engaging all your senses, and the greatest part about rock ’n’ roll and music is that it’s rhythmic and nighttime—but it is erotic, and it was just so—irresistible for me, so freeing. And then to have Lobi invite me to sing and play with him, and just to go to the depths of the deepest Chicago and Delta blues, it was just the most natural thing in the world.

“IT’S THE RESPECT AND APPRECIATION AND RELATIONSHIP THAT PEOPLE HAVE IN AFRICA, AT LEAST IN MALI, WITH THEIR OWN MUSIC THAT IS SUCH A DELIGHT…. IT’S NOT ESTRANGED FROM ITSELF. IT HAS A PLACE IN THE CULTURE OF HONOR, AND IT’S CHANGING AND BEING FED AND NOURISHED. IT’S A MOVING RIVER….”

Q: Could you go back to what you said about finding some point of connection between Lobi’s music, or Bambara music, and something about blues that touches you, can you explore that theme a little more?

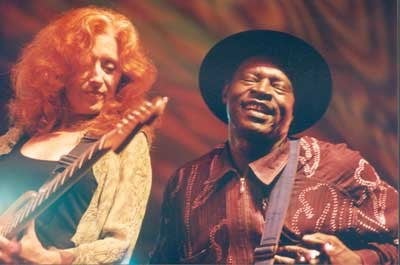

A: I don’t speak from an academic point of view, usually. For me, it’s all feel. Ever since I first heard Ali Farka Toure when we played together at the Winnipeg festival around 15 years ago, I was turned on to the first batch of Malian music and I was riveted. I absolutely could not believe that something as close to Delta music existed in Africa—the kind of blues that most gets me is Robert Pete Williams, Fred McDowell, Skip James, Son House, John Lee Hooker, the really dark, lonely music—and here it was, mirrored back to me, in the music of Ali Farka. So to go to the country where this is from, having done a little education and reading, and find someone who’s a purveyor of a more modern outcropping of that . . . keeping one foot in the traditional… very evocative, dark and stark . . . haunting, lonely and sexy . . . all those things John Lee Hooker’s music brought out in me. To find also that almost sunny rhythmic expression that his guitar has—it’s not a stark sound, not coming from such a painful place. Interesting marriage . . . to have dance music and that evocative haunting sound mixed together like you get in Arabic music.

The influence of the music from that part of the world has filtered in and I understand. And that’s what made me want to go to Mali. It was an amazing thing all the way through my journey to hear that reference, and I would love to be able to have John Lee go over there. He would shake his head and just go, “Man, oh man.” I’m pretty sure that he and Ali Farka are friends now….

Q: Let’s talk about Oumou Sangare for a minute: We did see her perform with her big band; what was your perception of her?

A: Her band was astounding, absolutely astounding. I’d seen her play a couple of songs in San Francisco a year before. Unfortunately we got there too late and only caught the tail end—it turned out there was only one show— so I didn’t get to see all the subtleties I got to see at the concert in Bamako. Her guitarist, Baba Salah, and the whole band just floored me, not to mention the dancers and the

singers. But Oumou herself is so .. . diva— in the best sense, not in the stuck-up sense. She’s just regal, dignified and gorgeous and luxurious. Because I don’t speak her language, I couldn’t catch all what she was singing about, but having read her lyrics from her album, knowing what she’s writing about and that beautiful, haunting ballad she sang, was just heartbreaking.

So to get to hear her sing in concert, after having gotten to know her and having been a fan for so long, was just an incredible gift. To know that she and Habib were honoring the AfroPop group, and Jackson Browne and myself—Habib and Oumou had organized a special show just for us in Bamako on our last night—it was an experience I can’t really put into words. She’s younger than me and yet— I bow to her, I honor her. I just feel incredibly respectful and appreciative of what she is and what she’s meaning to the world. Anything I could do to promote her would be my gift.

Q: Let’s talk about Habib Koite, in terms of your experience in seeing him play.

A: Habib’s album on Putumayo a few years ago just knocked me out. It spread like wildfire among the musicians’ community. I found I was going to be off at the same time as WOMAD last year [1999] and I literally flew up there just to meet Habib and Oliver Mutukudzi. I was just floored by the band … both bands, and I had a wonderful time. That really whet my appetite for going to visit him, and I told him we were trying to organize a trip and he says, “Come on, I’m going to be there!” That’s when the die was cast.. when I went up to WOMAD.

When we went to Bamako and he met us at the airport with Oumou. I was absolutely floored. When I walked out and saw they’d taken the time to do that, that it meant as much to them as it did to us, I was just in love with the country from then on.

Habib is the most generous, loving and unstuck-up person in his position that I’ve ever met, and my admiration for him is boundless at this point. To watch him delight in all these little places where he was getting recognized—he had accompanied our AfroPop group on our excursion upcountry to Dogon country and Timbuktu—and was so surprised and he would just get out his guitar and just play for anybody. Or sit in with all these bands. It’s pretty gracious, I think, for somebody that’s a big deal….

Q: What about when you saw Habib’s performance in Bamako?

A: I’d seen them up close at a rehearsal early in the week. That’s when I was really zoning in on their musicianship. I’d studied them on cds and at WOMAD and then went to see them last year at Yoshi’s in Oakland. I was just blown away by their spontaneity and freedom in the tradition of the greatest jazz musicians. They are totally in it.. in the moment. It’s not an intellectual process . . . it’s totally integrated. And that’s something that thrills me about Bruce Hornsby and other artists who are able to extemporaneously dip into the deepest tapwater and come up with the most amazing stuff. Like what Djelimady was doing. The greatest improvisers—you have to have your roots in some very, very deep practice and tradition and done your homework to be able to have that kind of freedom. . . . That’s the thing I most took away from Mali . . . the ability to be totally present in the music … listening and totally alert. Ready to go anywhere at any moment and feeling your entire spirit engaged.

Q: You’ve been around a lot of musicians, your heros like the blues musicians you were fortunate enough to hang out with in the ’60s and ’70s, you saw how they lived and how they worked, and how they traveled and so on. I’m just curious about your impressions of the African musicians, their lives, how they live, how they work.

A: Music in Mali appears to be more of a living, breathing part of the culture, and in a different place, than in America. There’s a weird cultural anomaly here where [basically] middle-class white kids are the ones to support blues musicians. Black middle, upper and working-class people in urban areas don’t flock as much to blues clubs or records, so there’s a unique kind of institutionalized racism that allows modern black culture to ignore its roots … not honor it because we don’t teach about it in school. There’s nobody saying, “why wouldn’t you want to listen to BB King?” [Sometimes it’s perceived as] their grandparents’ or great-grandparents’ music. I’ve heard it explained that it reminds them of poverty and an old backwards way before segregation stopped.

I understand the sociological reasons why this is basically white people’s music here and in Europe, but it’s a weird, bizarre thing. You can’t compare that to a country that owns its own music, and has always appreciated its own culture and celebrates it daily. Of course the French influence left a little of that Western cultural elitism, but on the whole, it seemed to me that Africans go to their own clubs and check out music in all its traditional and modern permutations. There’s a healthy club scene with djs playing international dance hits, but Ali Farka is also a god there. Habib and Oumou are as appreciated as Ali Farka Toure and Salif Keita … as they should be.

It’s the respect and appreciation and relationship that people have in Africa, at least in Mali, with their own music that is such a delight—that’s the biggest difference. It’s not estranged from itself. It has a place in the culture of honor, and it’s changing and being fed and nourished. It’s a moving river—it’s not a stagnant minstrel show. Not that blues is, but sometimes it can be used as a money-making thing to put on television to sell beer, commercials, jeans, or, any time there is a truck commercial there’s a slide guitar …. And blues fans in America relate to music as I’m relating to blues, or African music . . . that love is there.

For blues musicians to not be recognized in the whole of American culture with a place of honor like the Malians is frustrating. It’s very difficult for them as they often got ripped off—bad contracts, promotion—and now in Mali, they’re getting ripped off as well with cassette piracy. It’s very hard for local artists to make enough money to make a living or pay a full band from live gigs alone.

Q: How do you see your role in helping publicize African music?

A: I’d like to see my foray into world music not get turned into a fad in the major press, which is why I’m conflicted about talking about it much. It becomes trivialized, like the way the press handled Madonna talking about yoga. They cheapened the tradition of how wonderful it is, and belittled her too, like a media fad—“this week’s thing,” you know, and I don’t want any collaboration I may embark on to seem like “this week’s thing is Mali.” That’s just not what’s going on here, so I’d rather be doing interviews with magazines and radio shows and that are going honor the connection and not turn it into the flavor of the month, like the “Southwest Look” at Penney’s, and then next year, you know, “that’s so passé” . . . “Mali, that’s so 2000.” No, thank you, we’re going to be sticking with it.

I hear Malian instruments in my head already on a daily basis mixed with other things that I love that are Celtic and blues. Also with various dance beats and with a rock ‘n’ roll guitar tone the same way that the ngoni was amplified up in the dance in Timbuktu and it didn’t sound bizarre at all . . . it just sounded fantastic.

I’m coming from a—not saying this to be bragging—a pure place. I’m not trying to abscond with something new because I’ve run out of ideas. It’s not coming from a manipulative, Machiavellian, commercial point of view. I’m just coming at it purely from “Wow, I really like how that sounds. I think I’m going to go over there and listen to that closer for a while. . . .”

I’m following my muse, and my heart and my passion. And if I keep coming from that place, then whatever musical permutations come out of this will be as pure as the passion that made me want to pick up the guitar in the first place. . . ..

I’m fiercely protective of how this African love affair is portrayed and manipulated in the press, so I’m going to be very, very protective about it because I will not have that experience cheapened by commercial considerations. I want to be able to promote African music without appearing to exploit it. I don’t want them to be cheapened as this year’s fad; it’s more a meshing of all world music into a place of honor.

World music is here to stay—we can’t turn it into an “Entertainment Tonight” side story. It’s not a flavor, it’s blood. African music is blood and has nothing to do with fashion.

[Visit www.afropop.org for information on “Afropop Worldwide” and the Afropop tours.]

Rereading this piece in 2015 from 14 years ago, roughly the half-life of Afropop, is nostalgic in so many ways. First, there is the memory of Mali in those wonderful, hopeful days. The tragedies of recent years in this—among the most beloved of all the African destinations I’ve known—would have been unimaginable in 2000, when we ventured to Bamako and beyond with Bonnie Raitt. Our journeys and jams with musicians during three magical weeks in Mali was huge for all of us. Bonnie herself never fails to recall the experience when we cross paths. The musicians too are permanently marked by the encounter. And for Sean and me, it was absolutely one of the most glorious passages in the 27-year run of Afropop.

—Banning Eyre

A YEAR LATER. IN FEBRUARY 2001. WE GOT BACK IN TOUCH WITH BONNIE TO SEE WHAT EFFECTS HER AFRICAN ENCOUNTERS MIGHT HAVE HAD SINCE OUR FIRST INTERVIEW. WE FOUND HER ENTHUSIASM HAG NOT ABATED AND WAS DEFINITELY BEARING FRUIT.

Q: Can you now give us a hint of the direction the new album is going, in light of your African experiences?

A: I’m excited to be going back in the studio this spring with my co-producers again from Fundamental, Mitchell Froom and Tchad Blake. We’re going to be using my touring band for most of it. I can’t say there’s a lot of overt influence of African music … My taste tends to be quite eclectic, but fairly r&b/blues-based. There’s never a concept or deliberate direction on my records. For me it’s more a function of when I’ve found enough great songs that get me off enough to record. My band and I haven’t gotten together a lot this past year as I’ve been busy writing, traveling and looking for songs but I wouldn’t be surprised if some elements of Mali started finding their way into my music once we get back together in rehearsal.

I’m really excited about a collaboration I did get to do with Habib and his band Bamada last November, during their U.S. tour with Oumou. We went into the studio the day of their L.A. Conga Room show and cut a great song together. It was a blues tune Habib and I’d started jamming on when we got together with another writer friend, Annie Roboff, for a week of co-writing in France before his European tour last spring. I put some words and a melody to it and was thrilled they could squeeze the session in.

During Habib and Oumou’s tour, Jackson Browne (who’d also come to Mali to visit Habib, his trip overlapping ours last February), and I hosted lots of parties and sat in at their shows in Santa Barbara, L.A. and Berkeley. The tour was just a fantastic reunion for all of us and we had a ball cooking lunch together with Oumou at Jackson’s house, and showing everyone around L.A. We also invited lots of musicians and friends to see what all the fuss was about and of course, they went nuts as well.

Q: Can you tell us something about the song you recorded together?

A: It’s hard to describe how it sounds in words—but the feel is really compatible, but totally different from anything I’ve heard before. The mix of Habib’s guitar and mine, mixed in with what Bamada was playing came out very cool. I played a rough mix for Habib and the band when I flew up to Berkeley and they loved it.

It’s interesting, as what I would call “funky” and an r&b/blues-type feel is just not natural for those Malian guys. At first I don’t think the band quite got into the groove I was feeling, but after I went into the main room, picked up a percussion instrument and played the right accent while I was singing, they eventually got into it. So wild … a white girl from L.A. trying to explain a blues feel to young black guys from a place where the roots of blues began. Go figure. . . .

I’m hoping this will be the beginning of a lot more collaborations, both live and in the studio. Jackson and I are hoping to get back to Mali and do something to help with the cassette piracy issue, or any number of other things they could use help with. Oumou and I have talked about one day singing something bluesy together.

There’s also a chance I’ll be doing one of Oliver Mutukudzi songs on my new record. We tried to hook up last year during his trip to the States, but our schedules just didn’t mesh. I’m a huge fan and his new album is so terrific.

I’m hoping there will be more international festivals like WOMAD and wider exposure for shows like “AfroPop” over the newly expanded radio and satellite cable channels. There’s hardly anything more exciting than the possibilities of endless musical exchange, for us musicians as well as the fans. ★

Afropop Worldwide – Blues Reflections

tip: most convenient way to listen while browsing along is to use the popup button of the player.

Your Host is Georges Collinet

Afropop dives into a celebration of the blues–for some, the essence of the American experience and for others a link back into a lost history in Africa. For our program, we also went back through a number of key interviews we’ve done in recent years where the subject of blues came up, particularly in reference to the genre’s African roots. This feature presents extended excerpts from the interviews we presented on the program, and a few others. [Produced by Banning Eyre, originally aired September 3rd, 2003]

Featured Artists

- Ali Farka Touré

- Amadou and Mariam

- Bo Diddley

- Bonnie Raitt

- Corey Harris

- Lobi Traoré

- Robert Plant

- Taj Mahal

Bonnie serves on the Board of Directors of World Music Productions, the non-profit organization behind Afropop, which is dedicated to promoting recognition of the contemporary musical cultures of Africa and the African Diaspora. Bonnie’s deep respect and enthusiasm for African roots music and its profound connection to American music makes her a wonderful ambassador for Afropop.

“Back Around” performed by Bonnie Raitt with Habib Koite

Source: © CopyrightAfropop Worldwide

Afropop Worldwide – Mali Magic 2000

Afropop Worldwide – Blues Reflections

Afropop Worldwide – Youtube channel

Visitors Today : 6

Visitors Today : 6 Who's Online : 0

Who's Online : 0