Penny Valentine, Sounds, 12 July 1975

When Bonnie Raitt comes marching home to pack Carnegie Hall, Penny Valentine is there to talk to “the one woman who is a pure musician in the physical sense”

A SULLEN, warm, New York night and on the pavement outside Carnegie Hall kids hang out at interval time drinking cans of Coke, lighting up cigarettes in the dusk, overspilling into the 57th Street traffic that rumbles past.

These are blue jeaned babies hitting the New York concert scene en masse. It’s a surprising sight — like the West Coast has come adrift and floated across to the East. There’s a lot of blonde hair frazzled over quick tans caught at the start of New York’s heatweave Summer; a lot of downtown kids come uptown for the evening; Village kids sashaying their jeans and embroidered smocks around the luxury belt. These are college kids mainly — middle class radicals on an identifying trip.

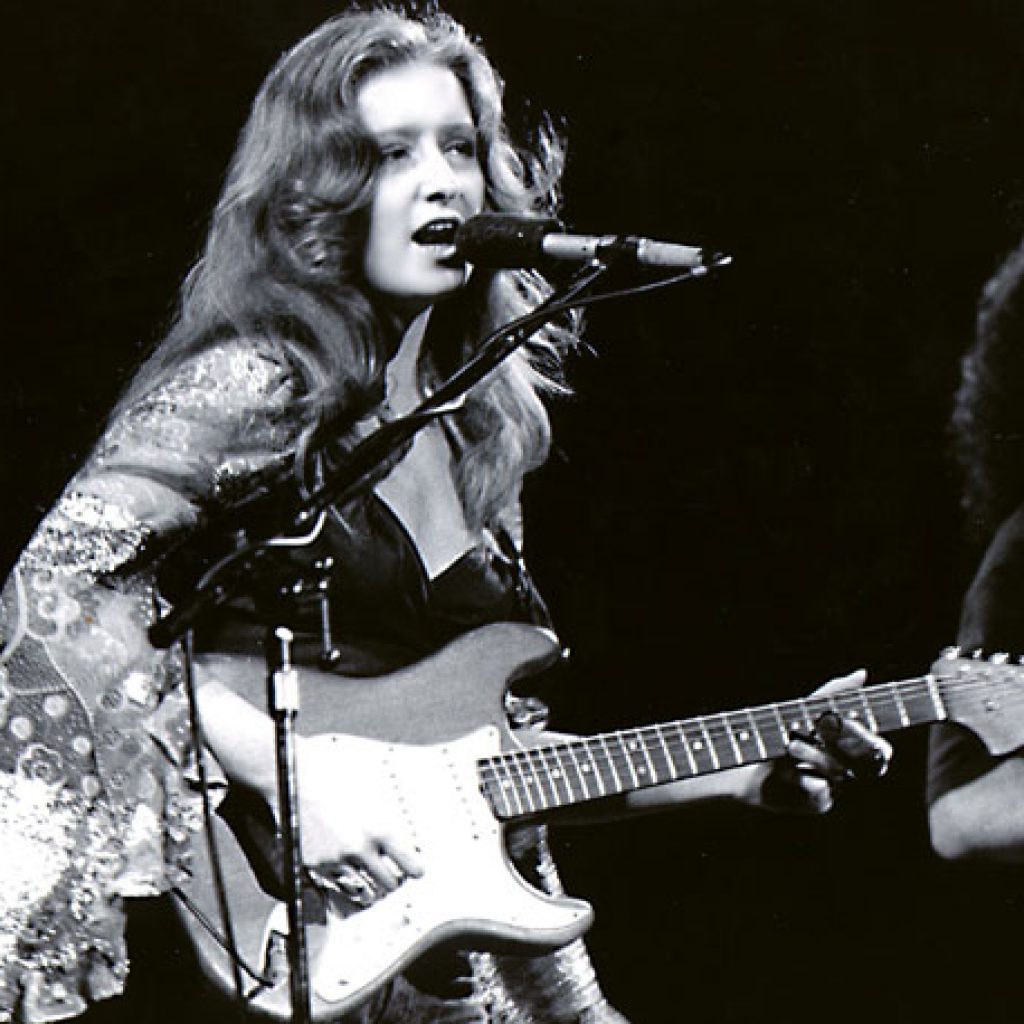

The girl they’ve come out to see is Bonnie Raitt and at 9 pm Martin Mull — an our man in Havana look-a-like — introduces “the most talented female singer in America”. Out on to the same stage that Billie Holiday finally made it 30 years ago, to sing her black woman blues to a rich white audience, comes Bonnie Raitt — a well off-white girl with her sad woman blues. A girl who sings lost and found with a rare brilliance.

Over the past couple of years Bonnie Raitt has produced four albums. An inconsistent talent on record, mainly due to production difficulties, Raitt is still, in my book, the best of the contemporary women musicians. When she does make it, when it all clicks in the studio, she can cut through you and expose your emotional nerve endings until you mentally scream for help.

It is an all too rare quality and when it shines through (as it does on Taking My Time, her best album to date), to say it’s worth waiting for is an understatement.

So here’s Bonnie up on stage. Oh, Bonnie what you done to me over the past year… and I’m not alone obviously. The kids that have come to Carnegie and packed it out through the stalls to the ceiling stand and cheer as she walks on stage looking easy and relaxed. Then they drop back into their seats, draping their blue jeaned legs over those hallowed upper balcony and box rails.

Next to me a group have managed to smuggle a gallon jug of wine past the strict security boys. By the time they’ve emptied it and consumed five joints and given out with a few ‘sheeits’ Raitt is up on a wooden crate, legs astride, ready for work. And Carnegie Hall — normally a pretty stiff veneer to crack — is laid back and ready for action.

On stage, Bonnie’s band work alongside her, neatly tucked in. There’s Freebo, a great mass of hair and her longest serving sidekick, on bass; young, slim, black Dennis Whitted on quiet sifting drums; Jai Winding hunched and weaving over his keyboard; and LA-tanned Will McFarlane swopping lead and rhythm guitar work with Bonnie on each number.

Relaxed

The whole outfit is young and they work with a relaxed, workman-like quality which would lead you to believe they’d been doing this stuff together for a decade. In fact McFarlane and Winding (son of jazzman Kai Winding), have only been with the band for a few months.

“When I started working in ’69 I was on my own. I was the all round cheap, non-threatening opening act,” Bonnie Raitt reminisces a couple of days after the show. “Then I bought in Freebo so we could build things a little — me on acoustic, him on fretless bass.

“I didn’t want to take a band round right away just for the sake of it. I wanted to wait until I was sure I was making enough money to know I could always pay them.” She added drummer Whitted two years ago and last September, for a 50-city Jackson Browne tour of the States, brought in McFarlane and Winding.

It’s very much a band unit. In fact the most surprising thing at Carnegie is to realise that on her live work it’s Raitt the musician rather than Raitt the voice, that hits you so hard. It takes some mental adjusting to.

On record I’ve always been most aware of that voice which not only swoops and chops on the few fast numbers she throws into sessions, but which also gives out so much pain and uncertainty. But tonight the voice becomes almost a secondary instrument to her guitar work.

Raitt is, among her contemporaries, the one woman who is pure musician in the physical sense. Whether it’s slide, 12-string, acoustic or bottleneck, her guitar playing drives across like a truck. She plays with a grinding, blinding, strength — moving her body at the same pace as her fingers slide across and hold the strings.

There’s some boogeying tonight which brings people on their feet and down in the aisles — courtesy of Wilson Pickett. But for the main, Raitt’s onstage material is culled from the kind of songs she has always had the most empathy for.

They’re songs that are the real root of blues. Her man is gone, her man is treating her bad, she’s a lost soul trying to make some sense of loneliness and pain, she’s back for more despite it all because when it’s good it’s stupendous.

She takes her numbers from right across the board. From the black music she grew up with and which set her on a blues path in the first place.

Contemporary

There’s Ray Charles’ ‘My First Night Alone Without You’, Fred McDowell’s ‘Write Me A Few Of Your Lines’, Mose Allison’s ‘Mercy’ and the songs of young contemporaries like Prine’s ‘Hard Way To Go’, Eric Kaz’s ‘Love Has No Pride’, his stunning new ‘Blowing Away’, and the chiding bring down of ‘Girl You’ve Been In Love Too Long’.

Tonight it’s the last which works the least. Raitt’s off her box without her guitar, standing in front of the mike and quite honestly looking uneasy. To suddenly see her away from the comfort of the instrument that becomes so much a part of her physically is to see her exposed. And the use of a directional mike means that one head sway and you lose the power of the words.

Conversely, Kaz’s ‘Blowing Away’, near the end of the set, is done alone and back on the box, and the sight and sound of Raitt bearing the whole weight of the song with her voice and guitar adds extra poignancy to the number.

It’s a spine tingling moment which makes Carnegie explode to bring her back once, and then, despite the houselights on in full flood, twice. If they had their way they wouldn’t let her go at all. But finally, with a laughing “you’re all crazy!” she leaves the stage for good.

“It’s a real strain to reconcile the private and public sectors of yourself in the business,” says Bonnie Raitt. It’s Monday morning and Bonnie is relaxing at her parents’ house in Westchester, an hour’s drive from New York City. “But,” she adds, “I think I’m more myself on stage than I am off.”

On the face of it, it’s an odd statement. Isn’t being up there part of the charade, the grease paint and the re-enaction of fantasies? Yet with Raitt it makes more sense. She does expose herself, body and soul, through the songs she performs. The mere choice of material encourages the belief that she strips down to real naked emotional honesty on stage, that it’s easier to express it through songs than day to day confrontations.

Raitt is coming to the end of a five week road stint and the time to relax from the pressure that brings — “and not having to see the inside of another Holiday Inn” — is welcome. She plans to spend a couple of days strolling the Westchester woods before she goes back to Los Angeles.

The paradoxes that now confront women in the ’70s — the ultimate freedom/shackles of freedom syndrome — find no better frame than they do in Raitt. In many respects she enjoys the ultimate freedom in the spotlight, coming over physically liberated at least. And yet, the fact that she’s constantly drawn to the wretchedness of emotional downers encapsulates her personal predicament better than anything else. You get the feeling that it’s this combination that makes her so attractive to her growing audiences.

Showbiz

She is well aware of this particular paradox but before it there’s the superficial one — the fact that Raitt came out of a show business background, the kind suspected of being more conducive to a comfortable, high income existence than the path it eventually took her on.

Bonnie Raitt is the daughter of Broadway musical star John Raitt. Born on the sunny side of Beverley Hills, she soon turned from the tennis court, swimming pool and beach set.

“My family tended to be pretty political anyway. They’re Quakers — like Seeger’s and Baez’s people — but probably more radical than most. I was brought up at a time when California surf music was king but I hated all of that. I hated the whole LA scene — the emphasis of getting a tan — it all seemed so empty. So the people I chose to hang around with when I was a kid were pretty pale,” she laughs, “and, I guess, soul rather than surf fans.”

Folk

Raitt initially started out by throwing her musical affections in with the folk stream. By 11 she was playing guitar as a hobby. She went to summer camp on the East Coast and found most of the leaders there were committed to freedom marches and peace corps work.

While her LA contemporaries were playing the Beach Boys and driving their Chevvies out to the Pacific, Bonnie was hunched over the radio grabbing as much folk — and then soul — music as she could find.

In 1963 Bonnie Raitt went to Newport and came face to face with Jimmy Reed and Muddy Waters. A whole new musical experience opened up to her:

“I went from the Miracles to Muddy Waters overnight — which wasn’t too far a jump. When I saw those guys at Newport I got hold of some Vanguard records and taught myself to play blues guitar just by listening to them over and over.

“I became a complete blues freak, but my guitar work was terrible. I mean that wasn’t the way to do it. I’d do all the wrong chords and play too many picks — I did everything wrong.”

Still Raitt’s involvement in music was very much a side line — something that ran parallel to her life but never took first place. As a child she had seen show business too close at hand to find many endearing qualities in it.

So, at 17, she moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to attend the superior Radcliffe College. There she took African Studies — planning to involve herself on a social and community level with the nations emerging in the Third World. But all along the line fate was marking her card.

A year into Radcliffe and a musician friend said why didn’t she come along one day and meet these people he knew. She went and was introduced to visiting bluesmen Fred McDowell, Otis Rush and Son House.

“It was the whole Chicago crowd. I hung out with them a lot from that day and I realised they were much neater people. I had a much better time with them than I did with people my own age. I was really lucky. There are a lot of musicians who never had the chance to be with those people and learn from them the way I did.”

When she left Radcliffe, Raitt moved straight into the club circuit. Though she was still trying to convince herself that what she was doing was a “hobby”, as opposed to a way of life, record contracts were soon being crackled under her nose.

“I didn’t particularly have this burning ambition to be a singer and a musician. People were always saying ‘you wanna contract? We’ll give you a contract’, and I was always telling them to leave me alone. I hung out as long as I could but finally it got to the point where clubs wouldn’t book you unless you had a record contract and there was money for advertising your appearance.”

Four albums later, Bonnie Raitt is now a committed musician “working with intent to learn”. She is also the new heroine figure — representing the current identifying predicament more than her contemporaries.

Bonnie Raitt is due back to LA to start work on her fifth album. So far, she agrees, the album she liked best was Takin’ My Time, her third, when she worked with Lowell George. But even that was fraught with hassles and went severely over budget: “basically because Lowell and I argued so much in the studio,” she laughs.

Butterfield

This time, following a less than satisfying sortie with producer Jerry Ragavoy, she’s optimistic about using Paul Rothchild who comes with a list of production credentials which includes work with Paul Butterfield.

“I think it’s going to be easier because Paul’s already proved himself as a producer and I think he’s going to be sympathetic to what I’m doing. It’s going to be, umm, kind of backyard with a little sophistication!”

She plans to go out on the road again in late Summer and wants to come to England hopefully with Little Feat in the Autumn. Meanwhile Bonnie Raitt, underneath all the outward security, struggles with herself and the inconsistencies which her kind of life pinpoints.

I ask Bonnie what she think’s music has given her and also what it may have taken from her personality. Bonnie, who up to now has been talking with double fast energy, suddenly sinks into silence. Then, after what seems like a long time, she finally says: “It’s given me… I want to answer this the best way I can… it’s given me… well I’m a night person and wouldn’t you rather work for a couple hours at night than eight hours a day?

“It’s a lifestyle which gives you freedom. After that I guess it’s up to you how fucked up you get. I don’t think it’s taken as much from me as it has from some other people. I grew up in a show business environment and so I didn’t get run over. I didn’t grow up looking at stars and wanting to have that. I was, umm, downwardly mobile if you like.

“If I’d been naive I could have got burned. I guess because of that, and because I didn’t particularly want to be a performer professionally, I was lucky. I know musicians who took five or six years of that shit before they found out what I was lucky enough to know before I started.

“What it’s taken from me on a personal level is slightly different. I think the hardest thing about being in this, and being a woman, is the position it puts you in personally. I mean no matter how liberated you feel or how liberated the guy you go with is, it’s difficult. Well let’s say I find it difficult.

“Yes I do get pretty lonely out there on the road, it’s no good denying it. Look, most men aren’t averse to picking up girls, it’s like a national sport, so the guys in the band have it okay. But for me — well it just doesn’t make any sense.”

Blues, said Bonnie Raitt earlier, is about men and women and feeling the hurt. Nobody has sole rights on that — black, white, rich or poor.

Pain

“I know some people are surprised, coming from my background that I took the direction I did musically. But pain is pain, and, if anything, coming from my background makes it worse. I sing about my problems and if my problems were concentrated on not being able to pay the rent then I could get it out that way.

“But they aren’t and that’s why I’m attracted to those bitter, sad songs — to get that personal pain out. When I’m happy I live it, I don’t sing it but when I feel pain the only way I can get that out is to sing it.”

© Penny Valentine, 1975

Visitors Today : 26

Visitors Today : 26 Who's Online : 1

Who's Online : 1