Issue #43 January/February 2000

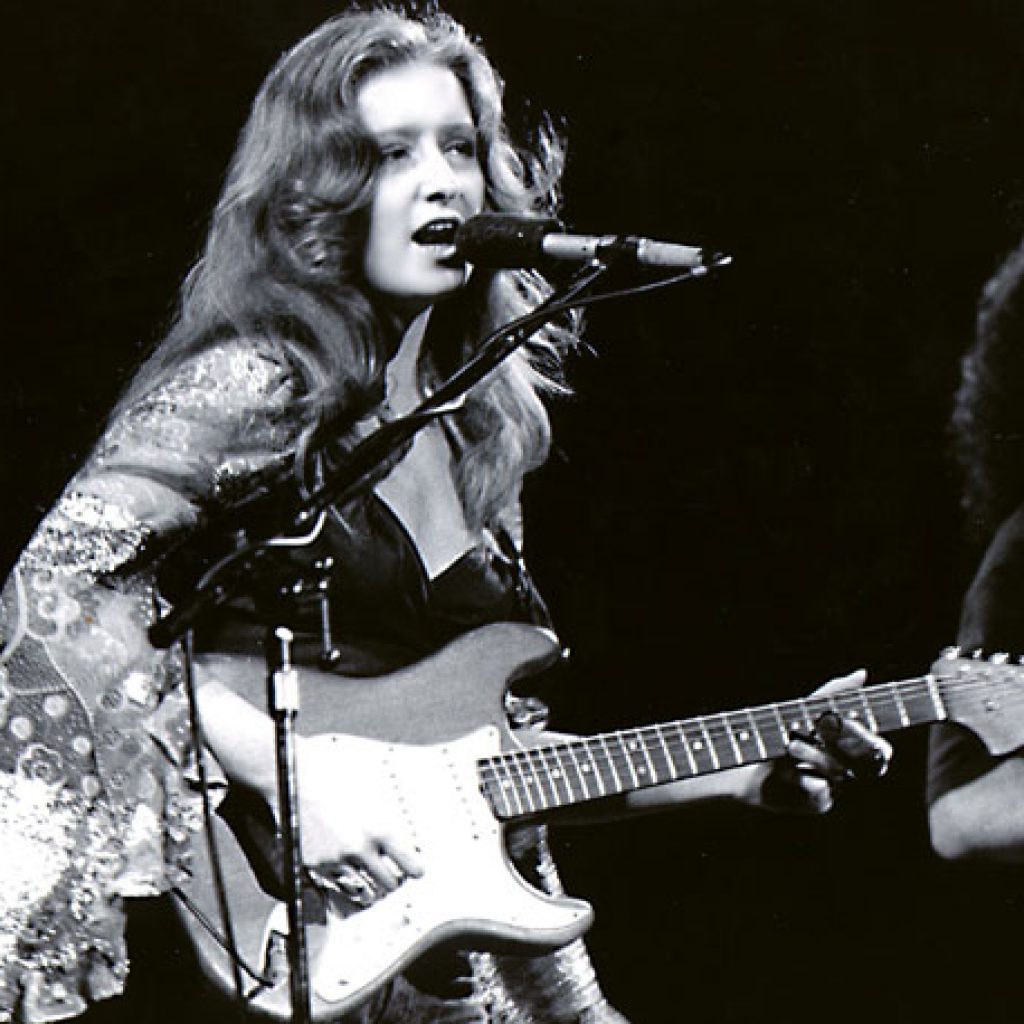

Let’s just put aside for a moment the fact that Bonnie Raitt is one of the most important musicians of this century, showing the world that a woman can wield a guitar while holding her own alongside the legends. And let’s ignore the detail that as a singer, this whiskey-voiced performer nails every note, and will move you wherever she wants you to go – to dance, cry, laugh, or sigh. And while we’re at it, forget that we’re talking about a truly great songwriter – one whose modesty tends to downplay that particular talent. Let’s just take all of those elements, wrap them up in a package, and put a nice bow on it.

Now step back and take a look. You’ll see that what we’re left with overshadows all individual talent and skill, and it’s something that should never, ever be taken for granted. And that is Bonnie Raitt, the woman who has made an immeasurable difference in this world and on the lives of all who are within her far-reaching touch.

Bonnie was born and raised in Los Angeles, the daughter of Marjorie – an accomplished pianist – and Broadway singer John Raitt (star of Pajama Game and Carousel). At the age of 8, she was given a Stella guitar and her life was never the same. “I was such a music fan that I played until my fingers bled when I was little, learning every Joan Baez record that I had,” she says. “And I then proceeded to learn what this thing was called bottleneck, which I’d never seen anybody do because nobody was playing it on TV. There weren’t any photographs of it or books written on it. And I literally found a Coricidin bottle, took the label off, and figured out it was an open tuning.”

In 1967 she left L.A. and moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts where she entered Radcliffe, only to drop out to follow her true passion which she had found in music. She began playing in local folk and blues clubs, and Dick Waterman – longtime blues aficionado – signed her and introduced her to blues legends like Howlin’ Wolf, Sippie Wallace, and Mississippi Fred McDowell. “I became kind of a quasi assistant road manager. I would help with the logistics of getting suitcases, and getting food and liquor set up in the dressing room, and basically hanging out with my heroes – never expecting to have ever met them, let alone become friends.”

Her reputation in Boston and Philadelphia led to a record contract with Warner Brothers, and between 1971 and 1986 she released nine albums before her deal came to an end. But the tenth album was the charm. In 1989, Bonnie re-emerged on Capitol Records with her Don Was-produced breakthrough album, Nick of Time. It topped the charts, sold four million copies, and won a Grammy for Album of the Year. (It was actually one of four Grammys that she won that year, with the dazed and exalted Bonnie making 1990’s award show one of the most memorable in its history.)

The winning streak continued with 1991’s Luck of the Draw, which included the hit singles, “Something To Talk About” and “I Can’t Make You Love Me.” It sold over four million copies and earned three more Grammys. Her last two albums have both been chart-toppers and critical successes as well – ’94’s Longing In Their Hearts and ’98’s Fundamental. And in March, Bonnie will be this year’s only female to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

But awards and accolades aside, what makes Bonnie so beloved is that throughout her career she has maintained a commitment to social activism and general kindness to others that few artists can match. Uniting social awareness with music, she has played hundreds of benefits to aid causes that cover nuclear issues, anti-apartheid, pro-choice and women’s rights, Native American rights, and environmental protection…just to name a few.

In 1991 she became a co-founder of the Rhythm and Blues Foundation and works tirelessly to raise awareness and money for musicians who were pioneers in the music industry, but were left destitute by unjust record deals and lack of health insurance. She also brings those overlooked heroes of R&B on the road to open for her, showering them with a deserved spotlight. In 1995 Bonnie set up a program with Fender and the Boys and Girls Clubs of America to develop the Music Education Program, providing disadvantaged youth – particularly young girls – access to instruments and instruction.

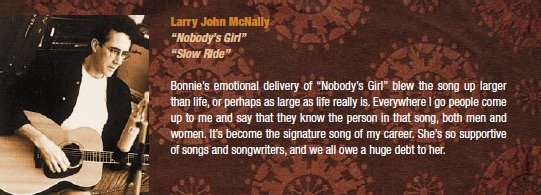

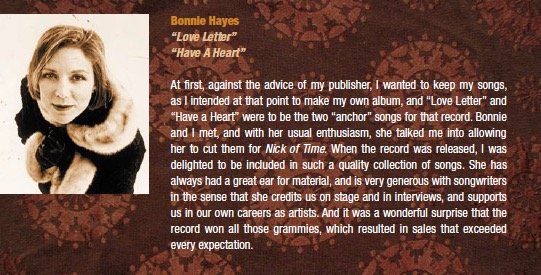

And even though she is a gifted songwriter (just take a listen to “Nick of Time”), she has become one of this era’s finest and most respected interpreters of others’ songs. She has a gift for finding those rare musical gems, all the while championing lesser-known writers and introducing them to a wider audience. In short, Bonnie Raitt has become the matron saint of songwriters.

So let’s bring the package back to the center of our view, pull out all of her musical virtues, and stand them up next to the plethora of work she has done to promote justice and improve the quality of life on this planet. Now we have a clear picture of Bonnie Raitt. A woman who’s changing the world. No doubt about it.

How did you first become aware of the plight of the rhythm and blues artists and their failure to receive royalties?

My friend, Howell Begle, is an attorney in Washington who has long been a music fan of R&B and blues, and he informed me that he had approached Atlantic Records to find out why some of the giants that they had recorded over the years still hadn’t received any royalties. Laverne Baker, Ruth Brown, The Clovers, The Drifters… So he formed the Rhythm and Blues Foundation from an endowment from Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun who is also a board member.

A $1.5 million grant started a program to help with medical and financial assistance for these R&B pioneers who were basically the victims of unfair and dated royalty practices. At that time, artists were supposed to pay the entire cost of all the recording out of approximately one percent – which was the standard royalty. And since then the record companies have sold and re-sold these masters to different labels without paying these artists. And even with new formats like CDs, 8-Tracks, and cassettes, there’s been no way that these artists could ever make any money. So 20 and 30 years down the line you have an entire population that is the foundation of our music business – rock and roll, soul music, and every other form of music that we all make our living from – who’ve still never been paid.

When I heard about the situation, I – and most of the people in the world – didn’t know that every time we bought a new Sam and Dave record those guys didn’t get a piece of it. And it not only was rhythm and blues artists, it was all artists that recorded before about 1970 when royalty rates were customarily low. When the era of the singer-songwriter came in, the high-powered lawyers and managers started to negotiate for a more fair royalty rate.

So then you became involved with the program?

Yeah. Howell approached me and let me know about the situation, and then I became friends with some of these artists and he asked me to be one of the founding trustees. Luckily for me, my success at the Grammys in 1990 brought me a lot more access to the media, so every interview I did was about royalty reform and about the situation from the time I was first involved in the foundation. I feel like I’m the town crier of the organization in terms of visibility, which was really, I think, almost why the Grammys happening at that time was so great – so that I could be able to publicize this.

What stage are you in with this program now?

It’s a long and painful thing to talk about, and there has been tremendous success and a lot of people have been honored, but I’m here to say that I wish there had been an industry-wide gathering of support to right the wrong of unfair royalty practices across the board. If EMI could take the million dollar hit a year to pay these artists while they’re still alive, then I think the other companies could have done it, too. Unfortunately, some have still not agreed and others haven’t followed through on their promises.

So it sounds like it’s whistle blowin’ time.

Yeah. You know, some people walk the other way when they see me coming. We’ve buried 60 people with the money we have. Some of those artists still went to their graves because they weren’t able to have a lifetime of health insurance. Pretty much all the greats except for a handful of superstars that have always made money have gone their entire lives without getting reimbursed for their work. And people like myself, Eric Clapton, Phil Collins, or Rod Stewart, who cover Motown and R&B artists, have an obligation to share our income with those that didn’t get paid the first time around.

So without working for royalty reform and sharing your income, it’s another kind of exploitation. (Pause) Sorry that’s so heavy-handed, but I can’t smile about people going to the hospital that have no health insurance. And that 91 million bucks to build the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is great, but there’s also got to be money for health insurance to pay for teeth and instruments and financial help for the artists that put that building on the map.

You were traveling with a lot of those great blues artists when you were in your twenties. What kind of influence did they have on you?

I’d say what I learned from them primarily was their history, what their lives were like. The oral history of having somebody talk about what it was like when I asked a million questions like, “Did you know Robert Johnson?” and “How did you get the juke joint to shut up and listen?” And they’d say “This is why we have this resonator in the guitar,” “Electric guitar was so great because suddenly people could dance and hear and then you could have drums and bass.” You know, I got this all first hand.

The great gift I got was their friendship and their tutelage in person about what it was like to be a black person in this century from that era, and how it felt to not have access to radio. Or when race records got off the radio when the war and the depression hit, how that made them feel to have to give up their careers and go be a farmer, or a Pullman porter, or a domestic, or in Sippie Wallace’s case just give it up entirely. Or to have white artists come and get a bigger hit off of songs they made famous. So it was more like life lessons on how to be a man and a woman, and lessons about love, and how to drink, and how to dress, and all that (laughs). It was a lifestyle, and mentoring that was as important as soaking up every lick that they were playing.

You were right in the middle of the whole folk and blues revival, weren’t you?

You know, there were all generations of young white kids that fell in love with blues in the late ’50s and early ’60s, and the folk music revival that was raging across college campuses and in England – this rediscovery of all these terrific folk artists, whether it was bluegrass or Bob Dylan celebrating the tradition of the Weavers and the political music of Woody Guthrie, and the labor movement…the bluesmen were rediscovered and it was just a fever to bring these guys out of the south. There were just tons of white kids with legends about Robert Johnson and Son House, driving down on their spring breaks with tape recorders asking everybody on a porch, “Have you seen this guy.” It was this fantastic exploration and their appetite was whet by these Alan Lomax recordings and the fascination with all things that were blues.

I was a little pre-teenager in L.A. and I just caught the fever. I couldn’t wait to get old enough to go to Greenwich Village and hang out with John Hammond, Dave Van Ronk, Bob Dylan, and Joan Baez. I raced to get to Cambridge in time to hang out with them, and then Club 47 closed my freshman year. The Rolling Stones also had a huge influence on my generation’s getting turned on to the the blues.

And it was an interesting thing the way that older black musicians who were suddenly brought back – and for the first time into national attention – played in night clubs in New York, Boston, Philly, and California in front of white people. For the first time in their lives they got record deals where there was national distribution, and there they were mentoring their surrogate grandchildren – 18-year-old college kids. Paul Butterfield played with Muddy Waters. Eric [Clapton] played with Muddy. And I studied with Fred McDowell and Sippie Wallace. And their own kids weren’t interested in learning about blues, because the blues was their grandparents’ music. It represented poverty and backwoods. Something they’re almost embarrassed about. American schools don’t teach appreciation of jazz and blues and their place in this culture.

So it seems that now you and a few of your peers have become the teachers to your teachers’ own grandchildren.

Yeah. You have this weird sociological leapfrogging where my own grandparents passed away when I was 19, but I inherited Sippie Wallace and Muddy and Son House and Fred McDowell, and that’s where I got my grandparenting – from them. And they probably really would have wished that their own children loved their music and took up in their footsteps, but because blues was negated from around the ’30s until the ’60s, the only people left to pick it up were the young white kids who romanticized black music and knew of the place in the culture it had.

So here we are going back, and now there’s a bunch of younger, black blues people coming up and saying to me and Eric and the Stones – as well as black artists like Robert Cray, Etta [James], Ruth [Brown], and Charles [Brown] and others that have been singing it – saying you turned me on to blues. You know, “I heard your records from the ’70s, and that’s how I got into blues – through you, not my family.”

Speaking of learning about music and it’s history, how important do you feel arts education in schools is to education as a whole?

I don’t know about your school, but I took art classes, music, and even P.E. for granted when I was in public school in Los Angeles. And I found out in the last decade that a lot of inner city schools don’t have P.E. anymore, let alone arts and music. The white flight into the suburbs has made passing school bond issues that pay teachers better and support arts programs in the schools, orchestras, and even current textbooks a thing of the past. I just couldn’t conceive of a childhood without an option to be in a school orchestra or the chorus or go to finger-painting classes or sculpture…I mean, it was always an option.

So, how important is it?

It’s so important to be a whole person to not just be studying math and English and science, you know? How can you negate the function of the spirit of the soul? The artistic expression – the whole artistic side of the nature within humor and pain.

There is no full well-balanced life without the ability to at least have those forms of expression. They’re not luxuries. It’s crucial. We’ve got to be able to raise money in the private sector or in government programs to put a high premium on being able to give kids that don’t have as much money the ability to have music lessons. The inner city clubs have got to have the right to do something other than listen to a beat box and rap. Where is the “new” Herbie Hancock coming from?

With the Music Education Program that you started with Fender and Boys & Girls Clubs, do you get to enjoy many hands-on moments?

Along my last year’s tour I had about four kids and their teacher come to most of the concerts in the cities where we have the program. They were my guests and I would meet them afterwards and show them my tour bus and calluses (laughs). I talked about how the F-chord is still so daunting for all of us, even now, and not to give up. And that to me is such a highlight, to know that when I’m playing my concert, that those kids are out there watching and getting inspired. That they see that a woman can wield a guitar, lead a band, and be comfortable up there. I think that modeling is more important on a confidence, soul, and a persona level than whether or not they actually want to start playing my songs or not. So that was a great moment of the human connection. I do really wish I had more time during the day to go to the clubs. That’s something that in the course of touring and doing five shows a week with political and radio receptions afterwards, it’s just not often possible.

What I do get is lots of letters, lots of video tape clips, and sometimes local TV news will cover the Boys & Girls Guitar Program. I got a wonderful video sent to me where I can hear the whole class go “owwwww” (laughs) when they’re told to play a certain chord. So I’m really proud of it and the program, and we’re working on a letter to solicit support from a lot of other women musicians. That’s the ongoing challenge, and to get other instrument companies involved – bass, amplifiers – my dream is to have the music rooms of those Boys & Girls Clubs stocked full of instruments, and open every afternoon and evening.

Being one of the first – if not the first – female endorser of electric guitars, do you think manufacturers are going to start recognizing women in this role?

I think they see a market… you know I haven’t interviewed them. It’s almost like somebody should organize a panel at the NAMM show where the different company representatives would actually talk about what they could do. It also sounds like a good topic for an article. Because, I mean, to be Whitney Houston or Celine Dion or Britney Spears you don’t need to play an instrument. So let’s talk about who’s a singer-songwriter that’s known for playing instruments. Lauryn Hill and Madonna and the women that write their own music – you never see them playing the instrument in their video.

I think that the keyboard manufacturers know that people of every race, color, and generation are buying them so they don’t need people to endorse their piano. And I think that because electric guitar has tended to be a male purchase item, that somebody like me was a good touchstone when I finally got successful. And I think now, in the last eight or nine years of my success, there’s been so many more women who are good guitarists…you know, Susan Tedeschi, Luscious Jackson, Meredith Brooks. Sheryl Crow is amazing and an instrumentalist, and Shawn Colvin is a great guitarist.

Do guitars need to be designed differently for women?

I think it’s more a question of scaling for size, not gender. I’ve developed some thumb joint problems the last few years probably from years of playing heavier strings, finger picking style. My right thumb from pulling up on the bass strings with finger picks, my left from pushing my thumb against the neck to play blues on a guitar designed for a man’s hand size. I can’t look around and see any other women who’ve been playing this style for as long as I have to ask if they also developed problems. Rory Block and I are the only lifers I know about, and I haven’t asked her.

I would like to see instrument makers consider making and promoting basses, guitars and even keyboards in ergonomically designed options for anybody with smaller hands. I know now they’ve made junior size guitars, but they didn’t market them in a way I would have known about or thought was cool enough.

What changes have you seen for women in the industry during your years in it?

Well, there was a definite limit as to how many women could be on a performing bill. And there was definitely a limit as to how many women could be played in each half hour on each radio station. I don’t think that they did it deliberately, I just think that was the general old boys network. On most of the progressive FM stations that I remember there were all these really cool women DJs, and they might have been able to play their choices. I mean, when it was free form radio you could play more – I wouldn’t have a career if it wasn’t for the disc jockeys that played me, and a lot of them were women. But I do think on commercial radio, you did have a limit – if there were already two Linda Ronstadt plays in an hour, I don’t think you were going to get Emmylou Harris. But I wasn’t successful on mainstream, so I don’t know what the policy was – I was shut out of that club.

What positive effects have you seen coming from the Lilith Fair phenomenon?

I think this decade, if anything, it’s almost harder to be a male than a female. The Lilith Fair was crucial in proving that people will go see more than one woman on a bill.

And also, Sarah [McLachlan] is to be commended so highly for walking the walk and donating a portion of each ticket for national charities. The consciousness with which she’s set up this organization and the way that the tour feels when you’re on it – the backstage vibe – is totally different than other tours I’ve been part of. And I think that it’s never going to be the same again. I think that the days of discrimination, at least at the front part of the stage, are over – or ending. And I would like to see that same thing happen for promoters and executive engineers and producers and editors of magazines… you know I’d like to see that glass ceiling raised.

You’ve covered the songs of some amazing writers and gotten their work out to a wider audience. I wanted to just name a few, and see if you could give me a quick response of that writer and what their songs mean to you.

Oh, God, it’s going to be so hard to summarize – these people are so important to me, and sometimes I’m not very articulate.

Well, let’s start off with one of our favorites, Paul Brady.

Paul Brady is certainly one of the most underrated of our brilliant singer-songwriters, and his melodic sense is the best of anyone I’ve heard. For me, where he’s coming from – his music, lyrics, and soul – are on a level of the greatest of songwriters. He moves me so much. He’s a real touchstone for me on the level of writing about mature relationships, writing about marriages and what it’s like to be in them in a way that other people haven’t.

John Prine’s “Angel From Montgomery.” What has that song meant to you?

I think that “Angel From Montgomery” probably has meant more to my fans and my body of work than any other song, and it will historically be considered one of the most important ones I’ve ever recorded. It’s just such a tender way of expressing that sentiment of longing – like “Hello In There” – without being maudlin or obvious. It has all the different shadings of love and regret and longing. It’s a perfect expression from another wonderful genius.

Mike Reid and Allen Shamblin’s “I Can’t Make You Love Me.”

I was just astounded the first time I heard it, and I knew I had to record it. I’m a big fan of Mike’s voice, and the two of them together wrote probably one of the most exquisite songs I’ve ever heard. And of all the songs in my career, I think that one is the greatest gift. Just the fact that I got to sing it and not someone else. I think it stands among the best songs ever written.

Chris Smither.

Oh, yeah. His following is finally growing in proportion to how talented he is. I’d still like to see him break through, and if we can open radio back up to the formats that progressive FM radio were famous for in breaking the rest of us that came out, I think that Chris is going to be revered as someone who has done incredible work all along. And there’s a complete influence of his guitar styling on mine.

We were close friends in Cambridge in the days when I moved off-campus in college – he lived right down the street. He was already very well established and respected on the East Coast folk circuit, and I got to learn probably closer to him than any other musician. I mean, John Hammond and Chris Smither are the guys that were really holding the bar for me. To also write modern blues songs – “Love Me Like A Man” and “I Feel The Same” are the two that I did, and they’re just cool in a way that’s the level that Lowell [George] would write. I just wish him so much success and wider recognition.

Richard Thompson.

He’s another one I think has a deserved rabid following, and I think he would be very uncomfortable with any kind of mainstream success. I love the fact that he’s free to do what he wants, and I hope that he gets to reach every one of those people in the world that could enjoy him. He’s totally unique – to be able to take that Celtic music root of that English tradition and take it into modern instrumentation, and his arrangements, and his sardonic and wry approach to things, and his incredible mixture of humor and irony… I know him, so I know his humor is on the surface but his heart is underneath it. He’s got so many complex shadings. Like other songwriters you’ve mentioned, he’s so far above pop music that I’m just glad he’s in that rarefied air. And as a guitar player there’s never been anyone like him.

One of my favorite songs, Gary Nicholson’s “Shadow of Doubt.”

Oh, I’m so glad – that’s one of my favorites, too. I had heard his music over the years – people naturally put us together in terms of publishers sending me his stuff for a long time. I’ve always really come close to cutting a couple of different things of his. I knew what a great guy he was from mutual friends, loved the way he sang, and basically I have my own collection of music of his – it’s almost like I have an album collection I have so much of his stuff. And “Shadow of Doubt” is one of the most extraordinary songs I’ve ever heard. I don’t even know how I can put into words what I feel about it.

Karla Bonoff’s “Home.”

She was in our circle of friends, and actually went to the same high school in L.A. but later than I did. I didn’t know her at the time because I went to the last two years of high school on the East Coast. She was so loved and respected by Linda [Ronstadt] and the McGarrigle sisters and Wendy Waldman – we were all friends and family in the L.A. scene in the early ’70s. And I just adored that song – and I love the way she sings her own songs. I gotta say that Karla breaks my heart every time she sings.

Since so many people make their own CDs now, is it making it easier or harder for you to find songs?

It’s getting frustrating. We used to be able to pick who would probably be pretty good by who got to make a CD. And now you can’t tell. Every time I get a CD in the mail I think this might be the next Sarah McLachlan or the next John Lee Hooker or the next Tom Waits, and I give it a shot – and a lot of times it’s really heartfelt and pretty good – but not anything I can do. And I just wish them well. But there’s a lot more songwriters out there than there are places to get played on the radio. So I honor that people spend the time to send them to me, but it’s getting harder and harder for me to wade through them because the volume is so huge. And I must say that it’s harder and harder to find songs that fit, which is why I’m trying to write a little bit more.

Is collaboration something that you find helpful in getting the creative process going, or is it daunting for you?

I’ve only done it very little. I co-wrote with Dillon O’Brian and Paul Brady and Oliver Mutukudzi from the influence of the song that he wrote. And then I worked with Beth [Neilsen Chapman] and Annie [Roboff], and that was all on my last album. The ones in the room with the people, it’s very daunting. But it’s something I’m going to get better at because musically my reach exceeds my grasp, and I really need drum machines and multitracking and other people to play off of sometimes, or other parts to play off of so that I can be freer to follow where the melody wants to go in my head.

Does being exposed to the type of writing that someone like Beth Chapman does open you up to new processes?

A songwriter like Beth, who is coming from such an astounding place that…I don’t even know how to grasp where…it’s another realm. And the reason I love reading this magazine is because people like that are such a mystery, and they should be a mystery, and yet they’re talking about the process and it helps you touch it a little bit. Touch it for your own self so you can access those tips and those perspectives in your own writing.

When you’re writing, does it help you to have certain writing tools to get things down?

With my particular type of guitar style, because I didn’t take lessons, I accompany myself but I know just enough guitar to play the song the way I want to play it. But sometimes my taste is much more sophisticated and I hear a lot of African guitar music that I’d love to play slide over, and then sing my own kind of bluesy Celtic folk melody over, and I have to have an ability to have those complicated mixtures of African, reggae, blues, and rock ’n’ roll drum parts in my head. I hear all this incredible synthesis of music that’s influenced me, and I need to be able to get it onto tape so I can put my parts on it. So whether that’s just me multitracking like I did on my last album in my home studio or not…

Did you practice your guitar a lot growing up, and do you still enjoy playing just for yourself?

I played in my room when I taught myself guitar all the time when I was a kid. Then at camp and at school. And in my twenties there was a lot more jamming with my friends and learning songs. Now, my musician friends seem to be spread out a lot and I mostly get to play when I’m either sitting in, learning, or writing new songs or rehearsing. I wish California were a bit more like Nashville and Texas in the way they seem to have a lot more guitar pulls and places to jam informally than California. It sometimes seems like when I go to a bar to see someone, I’m asked to sit in and do one of my songs or some blues with the band. It’s like the audience is expecting you to be that person for them. Sometimes I just want to be anonymous and sit in and learn. These days it seems if you get other musicians in the room, you’re either cowriting or paying people to learn your songs…wish it were more for fun.

But as a child you practiced regularly?

I listened to Pete Seeger, Odetta, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins…their guitar styles are what I learned. At least until I heard blues. That soon became an obsession. But I only got good enough to accompany myself on songs I wanted to sing. And I would say that’s pretty much true today. I don’t aspire to be a great player..but of course you’re influenced by those whose music knocks you out. For me, Chris Smither, John Hammond, Ry [Cooder], Fred McDowell and Muddy, Lowell [George] – these are the ones for me. Still are.

But playing’s just like singing to me – it’s totally unplanned. My interest is much more in picking great songs, putting them in great combinations – one next to each other, and arranging them in a way that’s completely true to how I feel and how I want to hear the drums and the bass on the song when you arrange it.

Do you feel it’s important for artists to play a role in the production of their own albums?

Oh, I think it depends on the artist. I’ve always found my own songs and basically pick a producer or co-producer because they’ve been making records I already love and I want to go in their direction for a while. We discuss which sound we want, which engineer, which musicians, narrow down the songs I bring in. By the time we actually get in the studio, they’re almost midwifing really. And it’s great to have that other set of ears and someone you trust, that “gets” you when you’re too mired in creating to tell what’s good enough. These days, I like to just get the right people and songs together in one room and let ’er rip. For me, live and unfixed is best.

What projects do you have coming up?

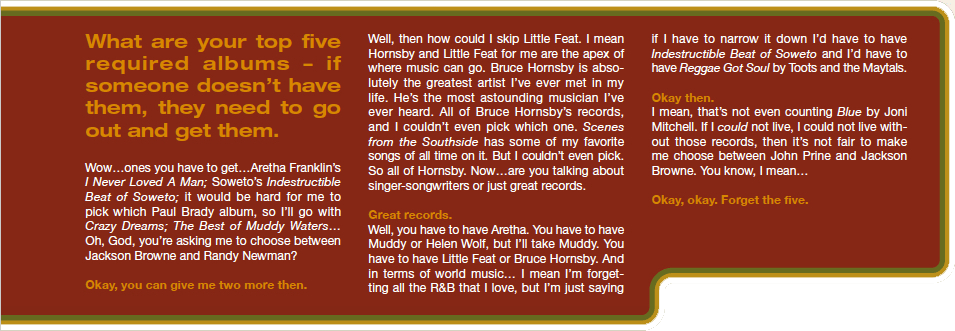

One of the things I’m really enthusiastic about doing in the next half of my life is to be able to cross pollinate musical styles in the way Peter Gabriel, WOMAD, Paul Simon, and even the Lilith Fair have been doing. My dream would be to have festivals, recordings, and TV shows based on some really interesting cross-cultural collaborations. Because that’s what I hear. I hear Paul Brady and Oliver [Mutududzi] together. Toots Hibbert and Altan. It’s something Lowell and I used to talk about. It’s what Ry, Taj [Mahal], David Lindley, and Paul Simon have been into all along. With the explosion of world music available to nearly everyone, it’s just a natural direction to be going in.

For me, World Music is just this never ending treasure trove that I get more and more excited about every day…and so to be on this last tour with Lindley and get to talk about Madagascar and all these places he’s been was great. I plan to do a lot of traveling in the next few years, soaking up as much influence and hopefully impacting those musicians as well. To be totally driven by the passion of the music that appeals to me. ■

More on The Rhythm & Blues Foundation

The Rhythm & Blues Foundation provides financial and medical assistance to Rhythm & Blues artists of the 1940s through the 1970s, as well as a support system to help identify other sources of assistance. Foundation grants have helped artists and their families cover the costs of emergency needs such as prescription medications, dental work, hearing aids, hospital stays and homecare, as well as assistance with burial expenses. To date, these programs have provided support to nearly 300 artists in need.

The Pioneer Awards Program

The Rhythm & Blues Foundation’s Pioneer Awards Program has recognized over 150 legendary artists whose lifelong contributions have been instrumental in the development of Rhythm & Blues music. This ceremony honors the career achievements of solo artists, vocal groups, songwriters and producers who are nominated and selected by members of our board of directors. As part of the Pioneer Awards, most recipients receive an honorarium. Since 1989, the Pioneer Awards Program has given over $1.5 million to worthy honorees and will continue to celebrate legendary Rhythm & Blues artists.

Doc Pomus and Founders Fund Financial Assistance Grant Program

Named in honor of the legendary songwriter and other founding directors, the program provides emergency assistance to any Rhythm & Blues artist who charted between 1940 and 1979.

Motown/Universal Music Group Fund

Established by Universal Music Group, the program provides grants to Rhythm & Blues artists who were affiliated with one of its labels from the 1940s through the 1970s.

Gwendolyn B. Gordy Fuqua Fund

Providing financial assistance to former Motown artists of the 1960s and 1970s, this fund was established by Motown Records founder Berry Gordy to honor the memory of his sister Gwendolyn, a talented producer, songwriter, entrepreneur and pioneering music executive.

Education and Outreach

The R&B Foundation brings together generations by offering Rhythm & Blues-themed educational and community outreach programs to the public. Whether it’s summer enrichment programs for elementary school students, workshops for seniors, panel discussions for music scholars or festivals for the entire family, the Foundation uses these opportunities to foster the public’s appreciation of Rhythm & Blues music. These events also provide performance opportunities for Rhythm & Blues artists.

Legacy Scholarship Award

The Foundation has established the Legacy Scholarship Award to encourage artistic excellence among future generations of Rhythm & Blues musicians. The annual award is intended to further the education and nurture the career development of aspiring young artists.

R&B Foundation Address:

5 Penn Plaza, 23rd Floor

New York, NY 10001

Phone: 1-800-980-5208

Fax: 1-800-980-5208

www.rhythmandbluesfoundation.org

For general inquiries, please email rhythmandbluesfoundation@gmail.com.

Source: © Copyright Performing Songwriter

- Women Changing The Face of Music

A Conversation with Bonnie Raitt - Bonnie Raitt’s Life of Giving Back to the Blues

- Come On in My Kitchen

Visitors Today : 49

Visitors Today : 49 Who's Online : 0

Who's Online : 0