by Andy Gill

Collectors of happy endings, look no further. Bonnie Raitt’s career was dumper-bound until a P45 from her record company inspired her to rediscover her musical roots. And now, as Andy Gill discovers, she’s got those ol’ Grammy Award-winnin’ blues.

All of a sudden, Bonnie Raitt was Number 1. After a career of close on two decades, it was hardly an overnight success, but so little had been heard of her since the early ’80s that when 1989’s Nick Of Time album hit, it hit with all the shock of overnight success.

Most people who cared thought she’d given up long ago, retired into that twilit hinterland of rock’n’roll memories. Since 1982’s Green Light, there had been a yawning silence from the first lady of the slide guitar, broken only by Nine Lives some four years later. The truth was simple and brutal: in 1983, Bonnie Raitt had been unceremoniously booted off Warner Bros, the first and only label of her career, in some corporate cost-cutting exercise. As it turned out, she was in good company: that Van Morrison was amongst her fellow bootees showed that the action had little regard for artistry or reputation, but was overly concerned with the bottom line. For Bonnie, it was almost a blessed relief, as Warners had long since ceased working effectively with her.

“I was just mad that they weren’t promoting my records.” she recalls. “I would rather get off the label than keep putting out records they wouldn’t promote. It was an unceremonious way they did it, though, because I had just finished another album and scheduled a tour, and the video was ready to be shot that week, and I was opening for Stevie Ray Vaughan the next two months, and they called up and said Van Morrison and myself and T-Bone Burnett and Arlo Guthrie were getting the axe because some corporate upstairs guy decided they had to cut the fat somewhere. After 16 years, that wasn’t the way to let someone go. But it was already an insult to not get played.”

The finished album was shelved, in an extension of the cost-cutting exercise. Eventually, half of it would appear on Nine Lives, but for the time being, Warners sat on it while she toured, without an album, for three years.

“I tour all the time, and 20 years’ following comes to see me whether I sneeze on record or not. But after a few years, my ability to draw without the advertising money from a new album shrunk, so I was down to playing acoustic concerts and just touring with a band in the summer for a few weeks, in the markets where I was big.”

Ironically, it was this enforced return to solo work that proved her salvation …

“I fell back in love with what made me different in the first place,” she recalls, “which is that I could play guitar and sing, and I didn’t need a whole crunching rock band behind me to sell a song. Pat Benatar might need a rock band, but I can just sit with a blues guitar for an hour and a half and do folk songs and great contemporary ballads, and not many people can pull that off.”

“They said Van Morrison and myself were getting the axe because some corporate guy had decided to cut the fat. After 16 years, that wasn’t the way to let someone go.”

She put this knowledge to good use when, after signing with Capitol, she hooked up with Midas-touch producer Don Was to make the album that would prove the most successful of her career. ‘‘Don and I decided that if I couldn’t make a song work with just myself and one instrument, it wasn’t the right song for me. That’s why Nick Of Time and some of the songs on Luck Of The Draw (her new album) started out small and grew.”

Most striking of the songs on Nick Of Time was the title track, a touching mid-tempo ballad whose subject – the maternal yearnings felt by single career women fast approaching 40 – seemed to strike a particularly loud chord among her fellow baby-boomers. As with several of her peers – Paul Simon and Neil Young most notably – she found her career reviving by chronicling the maturing process through which her generation was passing.

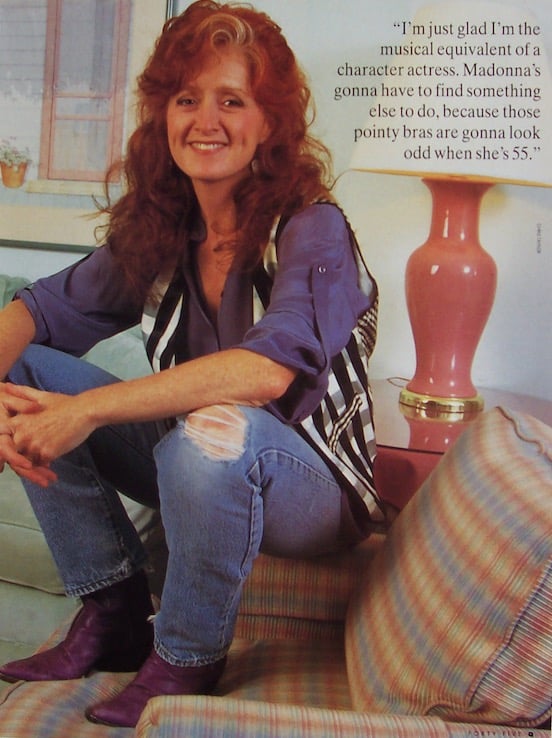

“I think it’s our job to write about what we’re going through at the moment,” she explains, “and being 41 I’m not going to write about the same things I wrote about at 20. I don’t think artists should be farmed out to pasture just because they’re in rock’n’roll. Elvis might have compromised his musical style a bit towards the end, but that doesn’t mean that artists from the rock’n’roll/folk-roots culture – of which he was not really a part – shouldn’t get better as they get older, like the great jazz or blues artists. Their experience deepens, and if you can continue to tap into that muse and have an audience that’s your age, there’s no reason why such as Sting and Don Henley and Jackson Browne, when they’re 65, shouldn’t be writing about what it’s like to be 65. And anyway, universal themes cut across all ages – otherwise, I wouldn’t be so touched by some of the older blues people.

“A lot of it,” she continues, “is to do with growing up and not getting soft and flabby; you can get tepid and sugary with your writing, or you can come to grips with things like relationships, as opposed to being single; how to keep a marriage vital: how to be dangerous even though you’re straight, have quit drinking and can’t stay up all night – those are issues about cynicism, about depression, about getting older, period, and what that does to your body and outlook. And of course the political situation is always worth writing about.

“There’s important issues at every juncture of your life. I’m just glad that I’m the musical equivalent of a character actress, because blues singers can keep singing and having an audience at 35, and someone like Madonna’s gonna have to find something else to do, ’cos I don’t care how pointy those bras are that she wears, they’re still gonna look a little odd when she’s 55!”

After years in the showbiz wilderness, Bonnie found several things had changed by the time Nick Of Time was released. Most importantly, the radio and MTV stations that had ignored her before had adjusted to fit her demographic. Where previously she had been a difficult artist to slot – part rock, part country, part pop, and perhaps too many parts blues – now her eclecticism and adult approach were perfect for VH1, the “adult contemporary” version of MTV; particularly when, out of left field, she won a Grammy.

“For some reason, my peers giving me that nod at the Grammies put me on the front page, and I got picked up by record stores that wouldn’t normally carry me because I didn’t get the airplay on contemporary radio. It’s only some fluke that my union should give me the vole – it’s only 6,000 people voting – that opened doors for me professionally, in terms of the number of people that were coming to my concerts.”

All of a sudden, Bonnie Raitt was Number 1.

Everything got easier when Nick Of Time was a hit,” she recalls. “I didn’t have to tour all the time – instead of crossing the country three times a year, I could do it just once and hit 15,000 people in one night. It was great. It meant I could have a personal life again.”

It also meant that she re-entered the pantheon of cause-conscious celebrities whose names are deemed big enough to attract audiences to fundraising gigs. A founder member of MUSE (Musicians United for Safe Energy), the US antinuclear movement, she has seen the entire showbiz cause/charity field grow and alter tactics since her participation in the first MUSE concert in 1979. In particular, she now sees ways in which the generally frowned-upon tour sponsorship syndrome can be put to good use.

“Now, you get somebody like Reebok sponsoring the Human Rights Foundation and giving awards to people who’ve been put in jail for standing up for what they believe in,” she notes. “So if you can get a healthy competition going in the corporate world as to who can be the hippest purveyor of an environmental issue, you can effect social change by aligning cultural icons with forward-thinking groups. That’s one of the sad things about blues festivals being sponsored by cigarette and liquor companies – it’s so ironic that the same thing that’s killing black people in the community is that which is sponsoring a black music – which most of them don’t want to hear anyway, it’s all white audiences nowadays.

“I have a lot of political organisations I want to help, and by corporate underwriting I can take more of my profit and give it to foetal alcohol centres and programmes on the reservation, to different environmental groups and so on. So in a sense, I’m using a corporation from Japan, taking their money and giving it to organisations from which our government has cut off aid. It’s a reshifting of resources.”

Being so politically active, it was only natural that she should be one of the first celebs called by Rita Coolidge to take part in a video shoot in downtown MacArthur Park to promote a charity song about the homeless in LA. The video never made it on to MTV – “I guess we were the second-string celebrities that never made it,” she says with a smile – but the event changed her life.

There, among the fabled cakes left out in the rain, she fell in love with Michael O’Keefe, the actor who seemed to be organising the shoot.

Best known over here for his roles in Caddyshack and The Great Santini (for which be was nominated for an Oscar). O’Keefe is the star of an American TV series called Against The Law. He was, she thought, both talented and cute; and perhaps most important of all, he shared the Celtic roots which had long been the source of much speculation for her. “Growing up in California as the only redhead in a family of people who could get tanned,” she explains, “I always thought I was left on a doorstep, and should rightfully be living in the highlands someplace, raising Shetlands.” After a tour of their ancestral homelands – O’Keefe Castle, in Malo, County Cork; and Raitt Castle, in Nairn, near Inverness they were married. At the ceremony, her father (the famous show singer John Raitt) wore a kilt to give her away, before the congregation adjourned to an Irish hostelry for the reception.

The revived interest in her Celtic roots is there for all to hear on Luck Of The Draw. Bonnie’s latest – and maybe best – album. Besides the couple of songs from Paul Brady, one of her favourite songwriters, there’s Phil Cunningham’s penny-whistle playing the Scots refrain to One Part Be My Lover, and the last track, All At Once, features bagpipes playing the refrain (actually the melody to Nick Of Time). But there’s also a renewed bite to her blues roots, which shine through as steely as ever in her slide-guitar playing. The blues remains, as ever, her first love.

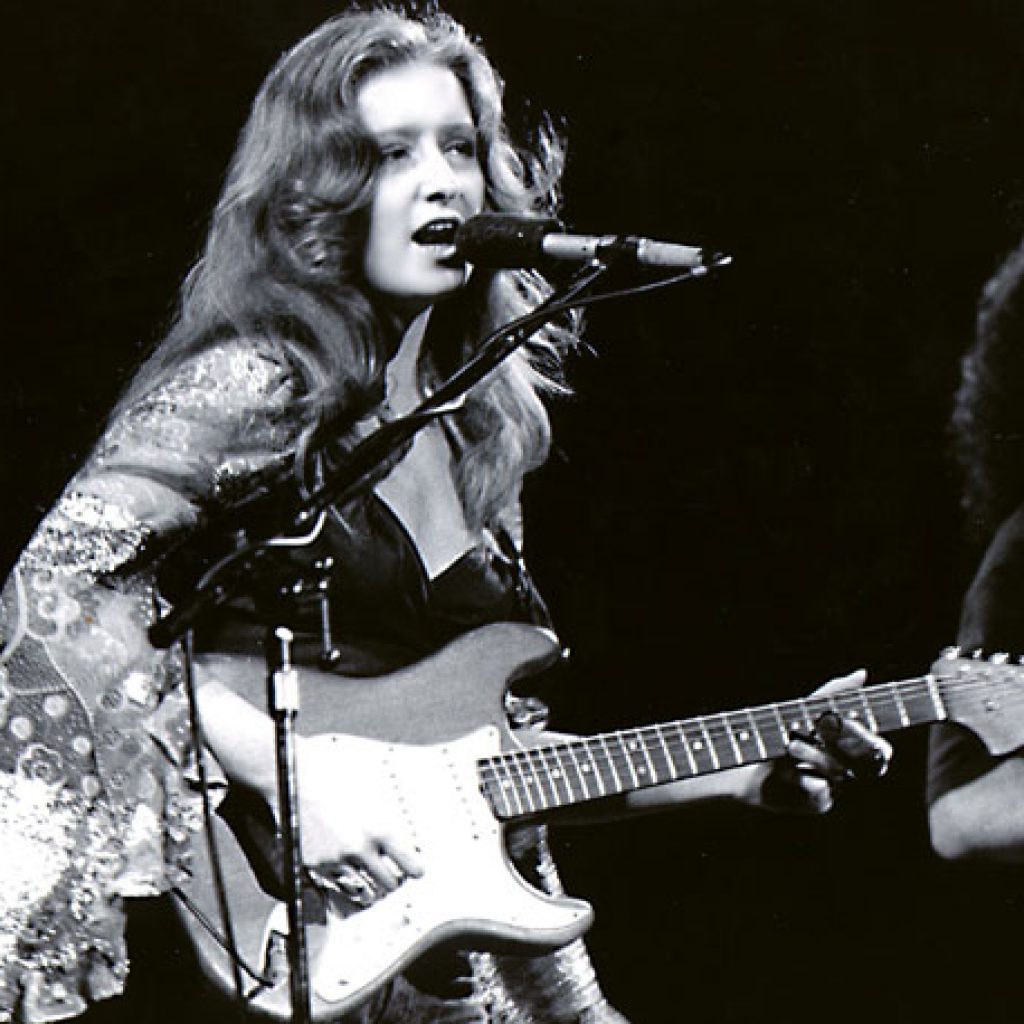

“I got to hang out with most of the old blues guys at blues festivals when I was 18 or 19, where I was the weird little white girl playing Robert Johnson songs,” she recalls. “They got a big kick out of the fact that a woman was playing slide guitar in the first place, let alone an 18-year-old round-faced redhead!”

Now that she’s finally achieved a sizable enough success, she’s determined to repay her debt to those earlier generations of blues artists, through her work with the Rhythm & Blues Foundation.

“It’s an organisation that started three years ago to help rectify an unjust situation.” she explains. “Which is that the pioneers of R&B in the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s – all the doo-wop groups, and artists like Lavern Baker and Ruth Brown – never participated in royalties because of the way the contracts were laid out then. They just got paid scale to sing an album’s worth of stuff: three hours’ work. Of those still around, some are in poor health, because they never made enough money to get health insurance.

“Now. with CD re-issues and all that, there’s a tremendous amount of income coming in for all those labels, so we’re trying to encourage the music business to contribute back. Even if they can’t re-write the contracts, they can do the right thing. And we’re trying to get artists, like myself, who make a living doing music based on that style, to take some of our income and give it back. We’re also trying to give those remaining artists some exposure – Sam Moore (of Sam & Dave) is on the new Bruce Springsteen album, for instance, and I took Charles Brown out on tour with me – because they don’t deserve to be put out to pasture any more than I do!” Q

Source: © Copyright Q Music Magazine

Visitors Today : 25

Visitors Today : 25 Who's Online : 0

Who's Online : 0